Once upon a time, once our vocal and neural apparatuses had evolved to a tipping point, our pre-sapiens, pre-Homo ancestors did something that changed our world. They made sound that made meaning.

The earliest ‘language’ was the ability to utter contrasting proto-vowel sounds. Which one might have been the first?

Was it u, uu, uuu—a coo, a huff, a roar? Was it o, oo, ooo—a moan, a call, a howl? Was it i, ii, iii—a chirp, a keen, a song? Was it e, ee, eee—a sob, a wail, a scream? Or was it a, aa, aaa—a breath, a sigh, a laugh?

In the Latin alphabet, such as we use for English, the vowel sounds are scattered among the consonants as if they’re all the same. And not all have names that match the sound they make. In abugidas or alphasyllabaries such as Devanagari used for Sanskrit, the vowel sounds come first. The consonants come later, in the order of where and how they are produced by the vocal apparatus. The consonants breathe through the vowels. They acknowledge their debt to the vowels—they pull into themselves a, and wear the signs of e, i, o, u above or below, left or right. Each letter is called an akshara, imperishable. Its name is the exact sound it makes.

Reading in an alphasyllabary creates activation in the left insula, fusiform gyrus, and inferior frontal gyrus (as with alphabetic scripts); the right superior parietal lobule (as with syllabic scripts); and bilateral activation in the middle frontal gyrus in line with the complex visual-spatial processing it demands. In other words, your brain lights up.

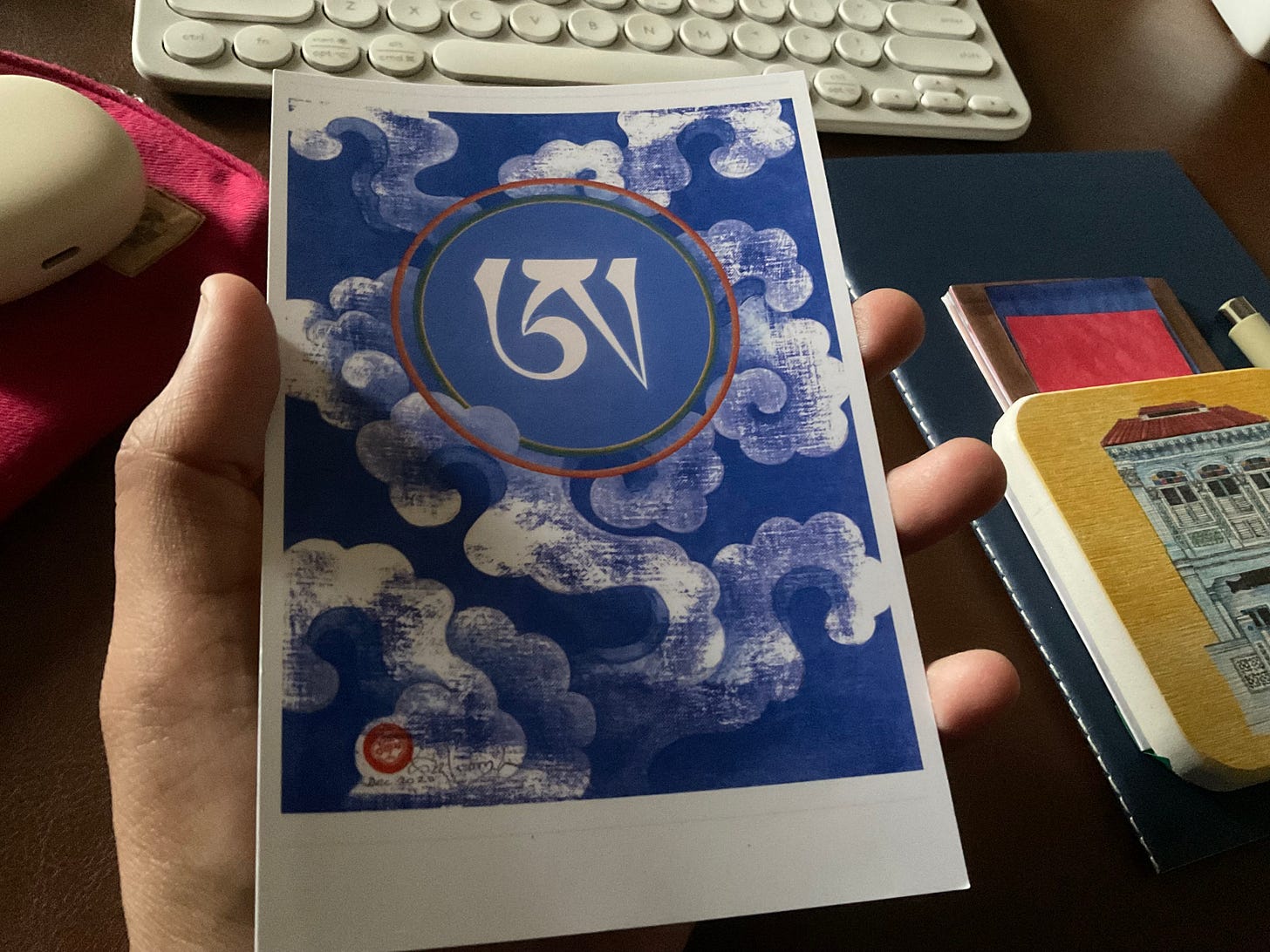

Image: The Tibetan syllable a in Uchen script. Halo Aa Amid Clouds, mineral pigments and palladium-leafed gesso on gesso board by Tashi Mannox, 2020. I’m holding a postcard home-printed from the small web image for personal use and admiration. Photo © Kanya Kanchana

#evolutionary biology #sound #vowel #consonant #alphabet #abugida #alphasyllabary #art #calligraphy